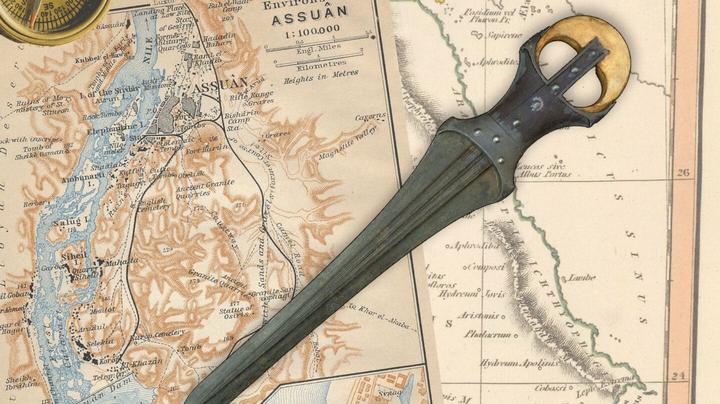

For nearly four millennia it remained clinging to the body of a deceased. It was a symbol of his owner's high rank and, perhaps, of his gall as a warrior on the battlefield. Camouflaged for millennia from treasure hunters, an Andalusian mission has found a spectacular copper dagger among the bandages of the priest Khema. A 28-centimeter jewel that inaugurates the series that El Independiente dedicates to objects discovered in recent years by Spanish expeditions in the land of the pharaohs.

The weapon, of which no similar specimens have been found in seven decades, appeared in one of the tombs of the necropolis that the team from the University of Jaén has been excavating for thirteen years on the arid hill of Qubbet el Hawa, in the current Aswan, about 850 kilometers south of Cairo. “When removing the mummy we saw that there was an object next to her pelvis that was not part of the skeletal remains. It was a dagger in a perfect state of preservation, ”explains Alejandro Jiménez Serrano, the director of one of the most traditional missions in Spanish Egyptology, to this newspaper.

The snapshots that accompany these lines are proof of the removal of a corpse that was buried around 1825 BC, in an undetermined period that includes the end of the reign of Senusret III and the first years of Pharaoh Amenemhat III in the palace. The deceased embraced eternal life from tomb QH33, one of the hollows dug in the mountain of Qubbet el Hawa to house the governors of Elephantine, a strategic border enclave between Egypt and Nubia. The large tomb was a funerary complex for two governors at the end of the 12th dynasty, which also contains five other funerary chambers contemporary to those of both leaders.

"We definitely opened the chamber and we had access to the magnificent cedar wood coffin as well as the trousseau," he recalls. “It was quite an exciting moment. It was the first time we had discovered an individual who belonged to the family group that had built the tombs we were excavating. It was to be face to face with one of those protagonists ”, he reels. After millennia of lethargy, resurrecting a dead person implies certain complications. “We dealt first with trying to consolidate what was left of the outer coffin where the inscription with his priestly title was.”

A very scarce trousseau

The coffins had resisted time with obvious ailments. “The outer coffin was made of local acacia wood covered in stucco and painted. It was very poorly preserved. There was hardly any area left where his title as a priest was mentioned. We had to apply a consolidant, wait for it to dry and then extract it without breaking because it was completely destroyed by the action of the termites”, says the archaeologist. The inner coffin, on the other hand, boasted better health. “It was made of imported cedar wood from Lebanon that was obtained from the missions that he sent to the king to the city of Byblos. The pharaoh redistributed it among the individuals who belonged to the Egyptian ruling class,” he adds.

The wood kept a surprise: the dagger. “In the groin of the deceased there was a strange object: it was a copper dagger with a silver, ivory and ebony handle. One of the finest and best quality examples found in Egypt”, boasts the researcher from Jaén. "It confirmed to us that the members of the ruling family of Elephantine had access to high-quality objects, which were surely made by the artisans of the royal palace," he slides.

"It's as if he were wearing it on his belt. What caught my attention is that it was located on the left side to be seized by the deceased with his right hand »

ALEJANDRO JIMÉNEZ SERRANO, DIRECTOR OF QUBBET EL HAWA

The position in which the knife had passed through the beyond was not, in any case, trivial. “It's as if he were wearing it on his belt. What caught my attention is that it was located on the left side to be seized by the deceased with his right hand”, warns the director of the mission. The second coffin confirmed the identity of its owner. “He was a priest named Khema who died around the age of 25 for unknown reasons, perhaps due to an infectious disease. He had Negroid features and was a very robust individual, ”estimates the project.

Siri, define how to turn Criticism into success! Mohamed Salah 👑 https://t.co/4QSiOYvJOk

— bass Sat Jul 24 19:56:40 +0000 2021

The dagger was one of the few members of an extremely meager trousseau, the norm in burials from the last stage of the Middle Kingdom. “He lived at a time when funerary customs changed in such a way that male burials are not accompanied by a diverse funerary trousseau. Apart from the dagger, unfortunately there were only a couple of anhydrite cups that were stolen in 2013 from a warehouse in Elefantina”, notes Jiménez Serrano. “The most striking thing is that when I picked up one of those glasses and, despite the fact that the stopper had disappeared, I was lucky enough to smell flowers, the original content of the perfume. It had a very interesting smell. Rarely do you have in an excavation in Egypt the possibility of smelling an ancient perfume.

An exquisite elaboration

The dagger, however, was the great treasure that dusted Khema's grave. “It is made of bronze, silver and tropical wood, probably ebony, and ivory. In that dagger what we have are, neither more nor less, products that come from outside Egypt. The bronze is imported from the Near East or Sinai. The silver probably comes from Anatolia (modern Turkey). The tropical wood came from the African tropical forests and the ivory from the Upper Nile”.

The exquisitely crafted piece features a bronze body while the handle is made of silver, ivory and tropical wood. Under its homogeneous appearance, up to five parts are hidden, from the handle to the spike-shaped body, perfectly assembled. The detailed study of the object has confirmed that there is no trace of use. Its presence and the quality of its finishes are inquiries into the status of Khema.

“It is an object for funerary use that will accompany the deceased in the Afterlife and will help protect him from the dangers that he may face. At the same time, it informs us of his social position. It is a minority that has access to a piece of such value”, emphasizes Jiménez Serrano. The dagger is one of the treasures of the exhibition dedicated to the Spanish mission which, postponed due to the spread of the coronavirus, hopes to open its doors next November at the Nubian Museum in Aswan. "This is the first dagger we have discovered in the last seventy years and with a serious archaeological context."

The thesis of the team is that Khema belonged to the high society of the time. "It is possible that he would not only have been part of the ruling family but also the retinue of the governors of Elephantine who led the expeditions to Nubia and southern Africa," the expedition notes. The internal coffin that housed the dagger together with the remains of the deceased is also providing part of the information that time erased.

"It is possible that Khema was not only part of the ruling family but also the retinue of the governors of Elephantine who led the expeditions to Nubia and southern Africa"

ALEJANDRO JIMÉNEZ SERRANO, DIRECTOR OF QUBBET EL HAWA

In search of the memory of wood

A study, soon to be published in one of the most prestigious journals in international archaeology, will shed light on the process of building the coffins. Dendrochronology, the science devoted to dating the growth rings of tree plants, has shed new light.

“A few years after this find, we found another coffin in another part of the necropolis. Both coffins had been cut from the same tree with which we have been able to establish a synchrony between two archaeological spaces that in principle would be difficult to connect”, argues the archaeologist. "What we do know is that the coffins were not made in Elephantine but probably in the middle of Egypt, although, unfortunately, these carpentry workshops have not been found."

The result is a vindication of the memory that was lost millennia ago. “Now we know that they cut down the tree, took out the planks and built two coffins. We have two people who received the same shipment from Byblos (a city in present-day Lebanon). It allows us to connect them very closely in time, surely linked to the same family”, murmurs Jiménez Serrano. Not all the riddles have been cracked. The dagger that rose from the dead still raises unanswered questions. "The question of whether the dagger was Khema's property when he was still alive or whether it was given to him for the afterlife cannot be resolved," acknowledges the director of Qubbet el Hawa.