Marcos Leonel Posadas Segura, promoter of the Mexican Communist Movement, reflects on the advances and mistakes made by the Mexican Communist Party (PCM), founded on November 24, 1919. An institute that was significant for its character internationalist, defending workers' rights and distancing itself from the Mexican Revolution.

It is notable that until its “dissolution” in 1981, the PCM was always close, linked in various ways, to the main events of the political life of this country.

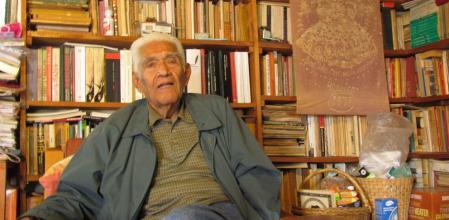

In an exclusive interview for the La Vanguardia Correspondent Readers network from his library in Mexico City, Posadas highlights the enormous damage that groupism has caused to attempts to build a truly democratic political system. By this, he refers to the petty expressions of tribes or factions, with a sectarian and dogmatic nature, which only seek particular benefits, to the detriment of great collective or national challenges. A phenomenon that is mainly nourished by clientelism.

Posadas Segura also shares his perspective on the current and future problems of Mexico. And he warns, as an important apothegm that, "history is not rectilinear nor is it made only by leaders."

—It is 100 years of the Mexican Communist Party (PCM), what is there to celebrate? What is there to commemorate?

—The central issue is to better understand and appreciate what the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) was, what it meant in the country's history. Important information has been hidden or distorted, and since it has not existed for some time, the PCM image has been distorted and blurred.

But anyone without prejudice can see that this ideological, political and cultural current was very important, that it made contributions to national life in different aspects. In this sense, it is not an exaggeration to say that much of what has happened in terms of progress or progress in Mexican society has to do, to a certain extent, with what the PCM has contributed.”

— How was the first stage of life of the PCM?

—The party was born in 1919, from a Socialist Congress held at the end of August and beginning of September. The Mexican Socialist Party was formed, which in a later meeting, in November, decided to become a Communist Party. This was the response to the call launched by the Communist International (CI) to the revolutionaries of the world. The CI had been formed in March of that same year, on the initiative of Lenin, a consequence of the triumph of the Russian Revolution in November 1917. It was a call for world revolution. By making the decision to be a communist and not a socialist, he was different from the socialist currents of the Second International. The agreement implied becoming part of the Third International and a member of a world party. The different parties in each country were national sections of the international party that had a central leadership. Here the triumph of the Mexican Revolution was very recent, of the power of the bourgeois factions that had defeated the revolutionary armies of peasant origin, basically Zapatismo and Villismo. The agreement to form the PCM implied taking a position before that brand new Revolution. Seen from afar, I imagine that they had to decide if the Revolution and the Constitution of 1917 were what had to be promoted. The answer does not arise as a conclusion from the Marxist theoretical examination that those few communists did not handle, it arises from class sense or instinct.

They said: “no, ours is another one that is about to take place: the worker-peasant revolution.”

In the years and decades that followed, the communists had to resolve their position regarding the course of the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1940. This fundamental phenomenon in the Mexican 20th century, even until 1960, was present as a political and ideological problem for the PCM. The first great task of the few tens of socialists who by class sense or intuition tried to make a new revolution was with what and with whom; from a weak, rudimentary theoretical preparation. In addition, very strong political differences arose that led to the rupture, to the division into two small parties: one headed by José Allen and the other by Lynn Gale; the first Mexican and the second North American. After months of prostration, a new unity was produced thanks to the authority of the CI and the vocation of the PCM to participate in the social struggle to organize workers and peasants. The PCM had another characteristic: its internationalism.

He took seriously the slogan of Marx: “Workers of all countries, unite”, since the working class is international, beyond the borders of States, nationalities and different forms of civilization. The class is one: that of the exploited and oppressed by capitalism. That is why solidarity with all peoples and the construction of unity in the struggle.”

Almost at the same time, the Communist Youth of Mexico (JCM) was founded in 1920, in which characters who were later very prominent, for example, the historian José C. Valadés, who left beautiful stories of those first steps; these young people were an active factor for the unification of the party. A character in the founding of the JCM was the young Alfred Stirner -he was an alias-, his brothers had a jewelry store in Mexico City, over the years he became an activist of the CI. Another, Edgar Woog, founder and leader of the Swiss Labor Party, made his first steps in Mexico, he began here.

From the early years a communist women's movement also arose. A very energetic, combative classist feminism, with its own publications such as 'La Mujer' and leaders such as Elena Torres and María del Refugio (Cuca) García.”

Since the first years, she participated in the congresses of the Third International, represented by comrades from countries like India and the United States. A Mexican representative in the CI was Manuel Díaz Ramírez, the second general secretary of the PCM.

—What were the flags, proclamations or demands of the PCM in those days?

—For those communists, the fight for unionization rights, to raise wages, was essential; matters of the first order for the workers. Another great demand was from the peasants: to win the land.

The revolution of peasant bases had triumphed, but the land was not delivered to them. Agrarian reform came later, preceded by many fights and bloodshed. The communist struggle had to do. It was strong to reorganize the peasantry that was dispersed and at the mercy of the leaders of the bourgeois revolution.”

In 1926, a National Peasant League was formed, with bases in struggle in various states of the country and influential leaders in various regions, among numerous fallen victims of caciques and the government such as Primo Tapia, Guadalupe Rodríguez, José Cardel... In certain periods, the communists took up arms against the riots of De la Huerta and later against the escobarismo. Guadalupe Rodríguez was a leader in the struggle for land and a peasant military chief. Calles, after making use of the armed forces of the communists, got rid of them, and Rodríguez was assassinated by direct order of the Chief. They were times of very hectic life, of confrontations. In 1927 there was the first great national railway strike and there were already communists such as Valentín Campa and Elías Barrios, who wrote the book 'El escuadrón de hierro'.

—Renowned Mexican artists and intellectuals were enrolled in the ranks of the PCM.

—It was fundamental. Characters like David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, Javier Guerrero and others formed his union of painters and sculptors. In 1924 they began to publish the newspaper 'El Machete'. This organ of the artists' union was handed over to the PCM, which made it their newspaper for more than 15 years.

Top artists in Mexican culture with worldwide projection who lived a very important creative period making public art. They were also activists to organize labor unions. Siqueiros formed unions in Jalisco and other places. 'El Machete' as a communist newspaper had a lot of presence and roots. There are precious photos where groups of workers and peasants listen to the reading of the publication that supported their struggles and formed their social conscience. And along with the party, it suffered a period of illegality.”

In 1929 there was a reaction from Callismo, the official party, the National Revolutionary Party (PNR), was formed, followed by a fierce persecution against the communists. They were outlawed. People like Allen were kicked out of the country, thinking he was a foreigner. He was no longer a leader, but they threw him out. Another almost legendary character was Julio Gómez. He came with his family from Odessa. Here he completed his learning of Spanish, became a worker and a communist. He was an organizer of the PCM in workers' centers in Puebla, Tlaxcala and became secretary of organization of the Central Committee of the party. And in the anti-communist wave he was expelled from the country. He went to Russia, worked in the CI and as a professor at the international communist school suffered unjust repression by Stalinism; he spent almost 20 years in concentration camps. Finally he survived and continued to be a militant until the end of his days. In January 1929, Julio Antonio Mella, a university and communist leader in Cuba, exiled in Mexico, was a member of the PCM and was its leader, was assassinated.

—And what happened to El Machete?

—It was successful, it filled a need, and it was published even in a period of great repression and secrecy. From 1929 to 1934 is the period known as "El Machete illegal". It was distributed clandestinely. Part of that time the newspaper was made in a portable press that changed places frequently. It was called 'The Dawn'. It was a support from German communists to the Mexican communists.

—Actually, the membership of the PCM, more than a mass party, in its beginnings, was modest.

—Yes, there were quite a few. But the magnitude of the movement in which they were immersed multiplied them by a lot. The 130 that were in 1926 directed organizations with more than 50 thousand active affiliates; the people from the workers' and peasants' organizations were brave. Already in the early 1930s, the Unitary Trade Union Confederation, the CSUM, and other organizational initiatives advanced in the industry unions; all this working together with other forces.

—How was the PCM's relationship with the Lázaro Cárdenas regime?

—When Cárdenas became president, the imprisoned communists were released. In 1935, faced with the offensive of the Callistas against the government, centered on their policy towards the workers that increased their already important mass influence, one of the slogans of the communists was: "With Cárdenas no, with the Cardenistas masses yes" . Then Cárdenas got rid of the three callistas and sent off Plutarco Elías Calles.

The previous polarizations and above all the repression against the communists led to moments of sectarianism; but in the new situation and with the agreements of the VII Congress of the CI that sought broad alliances against fascism, the political environment changed where political tolerance and the exercise of rights prevailed.”

For his part , the communists took advantage of the situation to advance the mass movements that contributed to the reforms of Cardenismo. For example, in the mobilization of the oil unions, communist work was present; also in the formation of the Confederation of Workers of Mexico (CTM) with its anti-imperialist program and deep reforms. This was essential for the situation of oil expropriation. There was a process of chaining of events, of changes in the relations of force. We see that history is not rectilinear nor is it made only by leaders. The oil expropriation was not the sole merit of Cárdenas. He was a filmmaker, but other factors contributed to that.

Later, the communists stood out in the defense of expropriation, they collaborated to dismantle the attempted insurrection of Saturnino Cedillo, financed by oil companies. In the agrarian movement, the communists promoted land actions and strikes. In 1936, those of the lagoon region; Also in the Michoacán haciendas of Lombardy and Nueva Italia, the social conflict was generated that Cardenismo resolved favorably. During this period, initiatives were taken to form the teachers' union and then the CTM, among various currents, with Vicente Lombardo as a very important left-wing union leader. The workers union arose with a strong presence of the communists because they were present in the main industry unions: miners, railway workers, oil workers, etc..”

This contributed to cardenismo having a left-wing direction. Cárdenas was a sensitive and renewing man, he promoted agrarian reform, peasant organization, oil expropriation and workers' organization, but under government control. Which was later paid too dearly: corporatism advanced and the political system was consolidated, which was subsequently perverted. That had a certain direction, but later it changed in favor of the private company.

—What other actions did the communists carry out in the 1930s?

—The party grew. At the VII Congress that was held at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, it was reported that the PCM already had 37,000 members. With a presence in many movements: in unions, in public education, in rural schools, with teachers dedicated to the people and in cultural initiatives. The new generation of artists and intellectuals made presence. For example, an important character was Silvestre Revueltas, a fundamental man for Mexican music. In the 1930s, the communists formed various organizations to promote international solidarity. Earlier, in 1927, the campaign by Sacco and Vanzetti was very important, and in support of the army headed by César Augusto Sandino —who was a PCM militant—, the “Hands Off Nicaragua” Committee was formed. The Anti-Imperialist League of the Americas was also created. And then the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists (LEAR), with characters like Juan de la Cabada and others.

Octavio Paz himself, in his first steps, was in communion with the left; as a militant and writer he went to Spain to an anti-imperialist congress, in favor of the republic. There was even a league of socialist architects who promoted workers' housing, the construction of hospitals and schools. There was Alberto Teru Arai, of Japanese origin, essayist, architect and anthropologist. In summary, in its first 20 years, the PCM made important contributions to the political life of the country against the top-down system, against the military leaders. The contribution of communism was not to pacify, but to civilize and give institutionality to a progressive State, with a social, democratic base; an issue that is still pending today.”

—What can be pointed out about the life of the PCM in the 40s?

—It was a dark period, a series of crises between the 1940s and the 1960s. Why did that crisis arise? For serious, strong political errors, for example, the policy that was called "Unity at all costs." What did it consist of?

After 1935, the slogan was to fight against fascism, which had been establishing itself as a world force oriented towards war and world domination. Another problem stemmed from Trotsky's exile and subsequent assassination. In two attempts there were communists involved. The first headed by Siqueiros, who proceeded on the sidelines of the match. The second attempt was made directly on the orders of the CI and Stalin. In Moscow, Trotsky was considered a danger because he displayed permanent propaganda against the power of the USSR; at the international level it was to weaken the greatest worker conquest and main bulwark against Nazism. This problem was addressed in a pragmatic and brutal way by Stalin: eliminate Trotsky.”

An emissary was sent to transmit the decision and have the collaboration of the PCM —remember that it was a section of the CI —. He met with the secretariat, the narrowest circle —three people— of the management: Rafael Carrillo, Hernán Laborde and Valentín Campa. The answer was “no”. It was explained that Trotsky was not a problem here, just an isolated, scandalous voice, but he does not represent a danger; and it was answered that they did not participate in that. Plus a moral argument: communists are not murderers. Other characters outside the PCM complied with that decision in August 1940. This refusal was followed by a barbaric reaction from the International. They created conditions for those leaders to be put in the pillory and expelled. An Extraordinary Congress organized by a Purification Commission appointed by the IC crowned the change of leadership in 1940. The expulsion of Laborde and Campa and many identified with them meant the destruction of a leadership that had been gradually forming for years. They were not just two individuals, it reached hundreds of party cadres. A new direction arrived, not improvised, but less apt than the previous one. It was headed by a labor leader from La Laguna, of agrarian origin, Dionisio Encina, who was at the head of the PCM for 20 years. It was a period with a succession of very serious crises for the party.

In the 1939 Congress, there were about 37 thousand members. In 1960, after the XIII Congress, when reviewing the real state of the organization, it was seen that we did not reach two thousand. The country had multiplied in population and workers, but the party had diminished tremendously. You had a lot of presence among intellectuals in the late 1930s, but by the early 1960s it was much reduced. In addition, the policy of destruction and the anti-communist and lying propaganda of the Cold War, applied here by Miguel Alemán Valdés since 1946, left no loophole. Anti-communism sought negative effects on the population: slander and isolate the “reds”, deny democracy, impose the worker-employer harmony agreed upon in 1945. It was a political basis for the capitalist revival begun with the Alemán Valdés regime.”< /h2>

The period of capitalist ascent was accompanied by a communist deterioration, moreover, complicated by internal processes, by differences that were not well resolved, channeled in the way that Stalin solved problems: with expulsion. There were three or four periods of expulsion and the emergence of other nuclei; that is, fragmentation. The emergence of the Popular Party headed by Vicente Lombardo Toledano, after the meeting that was called the "Mesa de los Marxistas Mexicanos" in 1948, meant the attempt to wrest the socialist banners from the communists. No one denied them that right, but deep down they entered into the dispute over the leadership of the communist movement.

The Lombard movement was linked to power. Lombardo was a very notable labor, union, political leader and theory maker. Together with sectors of the left of the official party and right-wing tendencies of communism, he formulated the idea that Mexico would move towards socialism through the path of the Mexican Revolution, taken over by reactionary groups that had to be fought; and that progressive sectors of the bourgeoisie and the official party should take the lead in this process. That vision made the fight for socialism conditional on how problems were resolved within the government and the official party. It was betting on a line derived from inter-bourgeois contradictions.”

At the end of the 50s there were three events that made it possible to change the course: the XX Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) , in February 1956, who formulated a series of important political theory theses. Two examples: the fight for socialism has different paths, not just one; and, the new world war can be avoided. This, plus Krushev's secret report criticizing Stalin's abuses and crimes, opened a period of reform in the Soviet Union in the early 1960s. Another great event was a wave of mass movements in Mexico against authoritarianism. and for better living conditions.

In April 1956 a national student strike broke out; It started at the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), but it spread throughout the country. The strike was crushed. Its leaders Nicandro Mendoza and Mariano Molina were jailed. The government imposed the direction of businessman Alejo Peralta, the Army invaded the student boarding school and spaces in Santo Tomás. And great union struggles of oil workers, teachers, railroad workers, telegraph operators and others followed, they made progress and were repressed.”

And in 1959 another great event: the “barbudos” made the Cuban Revolution. What did it mean? That the revolution can be made in the vicinity of the imperialist power and without communist leadership. It was a big wake up call. They were elements of the first order for discussion and to conclude that the PCM cannot continue as it is. An internal struggle was generated for fundamental changes. In the midst of mass struggles and repressions, minority critics became the majority.

This is how the XII Congress was reached, which resolved: in Mexico it is necessary to make a new revolution. That the path of the Mexican Revolution is exhausted. It was a change of great significance, an innovative position.”

A new leadership was chosen, the party's long period of crisis was reviewed, the methods that led to the division were criticized, the party was reinstated to Valentín Campa, and open to the entry of members of the other communist party, the Partido Obrero Campesino de México (POCM). There was an important change for the direction of the PCM.

—Did you start a new stage that goes from 1960 to 1981?

—With many events. As was the later stage, when the PCM decided to merge with other parties.

—And some of whose expressions may reach the present day?

—Yes, with expressions from then and new big problems, for example, the fragmentation of the Mexican communists, dispersed into groups with little influence. There were tremendous events such as the defeat of advances achieved throughout the 20th century, the end of the socialist bloc as a world project and the disappearance of the State and the Soviet system. But that does not mean the end of socialism as an ideological and political movement, and above all, as a historical necessity. But badly beaten as political forces, as an international movement; it also happened to the social democracy and the unions.

Capitalism strengthened itself and reached unsuspected levels, reorganizing the modes of production, seizing new technologies and extending exploitation to the working class in socialist countries. A very complicated process began in China, difficult to understand, with a Western mentality. A process illustrated with a phrase from Den Xiaoping: "Let the capitalist birds fly, but inside the cage." In other words, with the political control of the communists, take advantage of the productive and mercantile possibilities of capitalist methods. Which has to do with a fundamental theoretical problem that is present today: how the transition to socialism will be, given that it is a worldwide need. That capitalism that today is more influential, strong and dominant is also in crisis. It is traversed by insoluble contradictions. In addition, it has become a serious danger to the planet.”

In the framework of capitalism there is no solution to class contradictions or to the problems it generates: hunger, massive unemployment, migration, social decomposition ... New problems are causing crises: the excessive exploitation of nature proffered by the capitalist mode of production and which is attacking the regenerative capacities of the planet. It has caused risks such as climate change, the rise in the level of the oceans, environmental deterioration..., and previous problems and dangers are growing: armaments, the danger of an atomic war. Any conflict in any region of the world has behind it the risk of being a general war that will have to be nuclear. Large arsenals of nuclear weapons can wipe out life on the planet. Apart from other forms of mass destruction.

—During the period between 1960 and 1981, what events marked the trajectory of the PCM?

—The highest leadership, the party congress, launched the idea of making the new revolution. The idea excited the new generations, but we had nothing to do it with. Faced with this, several strategic initiatives arise. One of them is fundamental: to reorganize the mass movement, independently, in a democratic way, without corporatism or clientelism. With a new criterion: mass social organizations must be autonomous entities, not dependent on the parties; those built or directed by the PCM are not "of the party" nor "transmission belts of its policies", that is the Stalinist conception. You have to respect them with their own characteristics. The communists are working on it. They may be its leaders, but they are not its instruments. They are the property and patrimony of their members. A second big problem: rebuilding the party. How to do it? Arnoldo Martínez Verdugo made contributions that were key: working to establish a national leadership group, rooted in the localities, combining a movement from the center with the regrowth of local groups. And with it, constitute a new generation of communist leaders identified with the political line; on which the subsequent development of the party rested. With this, it was intended to leave behind the disastrous groupism.

Grupismo is characteristic of Mexican political life. Any individual, be it the president of the republic, state secretaries, department heads, a colony, a small power, has a group, cliques that manipulate. What do they live on? Of clientelism. It is an obstacle to the emergence of parties, of independent and democratic social organizations.”

At that time the policy of alliances was expanded; with which they participated in the formation of the National Liberation Movement (MLN), the solidarity campaigns for Cuba, the initiative to support the liberation struggle of Vietnam, of the Dominicans, Guatemalans and other peoples attacked by the imperialists. In 1963, important initiatives came to fruition such as forming the Independent Campesino Central (CCI) which denoted a serious crisis of the National Campesino Confederation (CNC); that is, of the official monopoly of the peasant organization. That same year, in May, the National Student Conference met in Morelia, the Morelia Declaration was approved, and the National Central of Democratic Students (CNED) was organized. There, very prominent communist comrades such as Raúl Álvarez Garín participated, and the force promoted by Rafael Aguilar Talamantes and Lucio Cabañas converged, after the bankruptcy of the Confederation of Young Mexicans in its 1962 congress in Guadalajara. Finally, progress was made in the task of reorganizing and democratizing the social movements deformed by the laws and corporate practices of the official party that impeded union freedom and imposed directives.

An important political fact of the PCM was to speak out against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops and other socialist countries. The PCM supported Dubcek's attempt to reform and his party. All of this put on the table the issue of the crises in the socialist countries, the way in which they functioned and the separation of leadership with a large part of the population. Problems that it was necessary to warn and urgent work to overcome them. The basic idea that socialism had to be democratic necessarily matured.”

In 1975, the struggle for democracy materialized in the task of demanding and winning the political rights of the PCM. And the idea that democracy could be a revolutionary path. The struggle for democracy was a constant line that marks this period from 1960. Another line developed: the independence of the party. We were born as a detachment attached to an international leadership center, the CI, which was maintained until 1943 when Stalin dissolved it. In the 1960s and 1970s we assumed that we were the only ones responsible for developing policies for our national process, directing movements, responding to the revolution in this country, because although the struggle is global, it takes place in each State.

It would not be the International, the socialist camp or “the Red Army of the USA”, which would make our liberation. It has to come from here. The concept of independence means taking full responsibility for the progress of the movement itself; No one would do those tasks for us.”

—How much independence did the communist youth have from the central committee of the party?

—First, there was line dependency out of own conviction. And two, it had organizational autonomy.

—Was the participation of communists in the student movement of 1968 of great relevance?

—We were totally involved, from its inception. But the terrible repression of 1968 crushed the student organization. In the following years, a sector of communist youth arose that concluded that the possibility of change was closed by peaceful means and began to look for other ways with weapons.

More than twenty guerrilla groups emerged. Most of them were surprised when they tried to organize. Many were denounced by infiltrators from the Ministry of the Interior.”

—Does it seem that the discussion in the 1971 PCM was very important?

—At that time, the question was raised: Why doesn't the party grow, despite so many efforts and struggles? What are we doing wrong?, or where is the cause? The internal discussion led to the theses of that year. One of the main theses was that the labor movement had not made its own theoretical elaboration. It had been working without theory. Dogmatism weighed too heavily. The transfer of formulas made for other places and other times.

The answers have to come from national conditions, from the history of this country. The theoretical elaboration must arise from the review of the experience of the movements of this society. It helps a lot what Marx, Lenin, Mao or Fidel Castro said, who made great contributions; but what is required is a theoretical elaboration for the revolutionary process itself.”

This type of theorizing explains the accelerated movement from 1975 to 1980. It allows us to fight for the idea of democracy, give the battle for party registration and the rights of the left, make alliances with Christians, Catholics —Sergio Méndez Arceo and other grassroots social movements. The PCM tried to have its feet in the concrete class struggle. Not in the abstract and timeless ideologization.

—Do you mean that the opening of the regime was not a free concession?

—The presidential election of 1976 demonstrated the crisis of the parties and the electoral system. How was it evidenced? For the nomination of a single candidate. On the other hand, hundreds of comrades were embarked on armed action and the regime in crisis thought of no other way to deal with it than with the "dirty war."

The solution that was found was to carry out the electoral reform. The characteristic of the 1977 political reform was that it was discussed directly between representatives of the Ministry of the Interior headed by Jesús Reyes Heroles and members of the PCM. As we refuse to submit to the above law; For example, to deliver the lists of members, they came up with the registration conditional on the result of the elections. We accepted it because we did not have the strength to impose our vision either. It was a stingy, mean reform, which has not yet finished, dosed for years through successive reforms. Today the demand from then continues in force: the need for a democratic electoral regime and the idea that democracy does not end with the electoral matter. There may be free elections, but that does not democratize the regime.”

This has to do even with democracy in the internal life of organizations and their relationship with the State, the strengthening of representativeness. Does the Chamber of Deputies represent the feelings and interests of the people? It does not represent it.

—Why did you decide to dissolve the PCM in 1981?

—No. We never determined the dissolution of the party. What was the decision? Generate a new party in unity with others. That is, merge different groups into a new party.

—So the word “dissolution” doesn't apply here?

—No. A disintegration occurred because the PCM was loyal to the idea of the merger. The other parties did not merge. They remained limited interest groups. Irresponsible and backward leaders like Alejandro Gascón Mercado's group and their attitude of gaining positions, put an end to the intention of forming a party of superior quality.

—Does it seem that grupismo has always been present in Mexican political culture?

—I think it's a cause of political backwardness. It has been historically. Interest groups manipulate and use collective assets and resources, impose political simulation, cause low participation of the population and discredit politics. So there are also no real matches. I believe that there were two attempts in this regard in the 1960s: the PCM, which made some progress, and the PAN, which tried in the time of Adolfo Christlieb Ibarrola, invoking the encyclicals of the Pope and the popular Christian movement.

Grupismo was one of the factors in the failure of the merger of the PCM with other parties. But not only for that, also within the PCM, groupism had emerged. Groups not ideological, but interest groups that only sought to enthrone themselves in power. The last agreement of the PCM was the expulsion of more than half of the militants in Puebla, due to an internal dispute over who would be the candidate for the Rectorship of the university in that entity. Within the party, the desire to be a deputy, municipal president, for positions of power, for group interests began to emerge.”

—And it seems that groupism continues to permeate political life today?

—In Morena, for example. Today there are two obstacles to organizing democratically: the groups of this old and negative tradition, and the other tradition of the single central leader. First, many people have come to that party, from the PRI, PRD and others, in search of positions. And they are succeeding even by displacing the founders. Putting the future of that organization at serious risk. If they continue like this, they will end up like the PRD. And secondly, to point out that Andrés Manuel López Obrador has great virtues. Without his presence, the change of July 1, 2018 would not have been possible. But it also has fundamental defects.

—The PRD could not overcome the groupism phase?

—He could not with the particular interest groups, factions, at the expense of the party that works and unites for collective interests. The PRI was also a federation of large groups subservient to the president, to the caudillo. A 19th century scheme, poison for democratic life. It is necessary, and it is fundamental to improve the present and the future, a democratic political regime. It remains to be seen if with AMLO and the 4T it is possible. It is possible, but it is not yet.

It is said that the system is no longer neoliberal, but how has it changed? The fact that scholarships or minimal redistribution programs are distributed does not change it. Or just by raising wages a little. This is how emergencies are attended to millions, it is positive. However, changing to neoliberalism has another dimension, they are mechanisms of exploitation and domination. The neoliberal context is global. It is not true that neoliberalism is over. It is much more serious. You need to locate the problem. This is hard? Yes.”

You will have to live with the interests of the Mexican oligarchy and the Yankees. Build virtuous political agreements, while continuing to fight and accumulate strength. To modify the economic system, for a time the State could be the center. Not again statism, but to gain space and share the direction that the oligarchy monopolizes and dictates; it implies a stage of struggle, of mobilization in favor of popular and structural solutions. One sentence is not enough: “That now is not the same as before”, it is true, but there is still no new political regime. There is new labor legislation, but the unions are still on the ground. If we want real and important transformations, a worker, peasant and popular base is essential. Not so much as followers of Andrés Manuel, but as promoters of a cause of great dimension. Another observation is that if the partisan and intellectual leadership of the 4T does not multiply, this will not continue. The example is the one that is used recurrently today: Benito Juárez. The Oaxacan president had a host of great people around him. Today they are not. It's only one. AMLO does human work, but it is not enough.

Furthermore, if society does not assume that the future is in its hands —not in the hands of AMLO, much less Morena—, that their autonomous participation is necessary to reorganize the communities and the nation, then society will continue to be prostrate. Patronage will continue to be the fabric that ties up loose ends.”

Our cause is not 4T, it is 5T, the socialist one; for that reason it matters that the one that is in progress goes well.

—What is your opinion of Arnoldo Martínez Verdugo?

—He is a fundamental political personality of the second half of the Mexican 20th century. He analyzed the problems, looked for solutions in a practical way, with a long-term vision. Many meetings that he chaired were very difficult. He proposed solutions, brought order, connected the dots. He established a method. Nor was he a superman. He was a type of leader who emerged from the working classes who contributed a lot. With the struggles of the second half of the last century, advances in political life were promoted, not everything that is needed; but it is important and it would not have been achieved without people like Arnoldo. Others showed off more or made more noise. Martínez Verdugo was discreet, modest, however, very fruitful in politics. And we must acknowledge the contributions of other very important communist leaders such as Valentín Campa, Othón Salazar, Ramón Danzós Palomino, Enrique Semo and more comrades.

—Enrique Semo has written a great book to explain the Conquest, do you think Spain and the Vatican should apologize?

—You have to apologize. They committed heinous crimes.

We must demand responses from the Kingdom of Spain and the Pope. The conquerors destroyed religion, identity and culture. Everything has to be re-examined and consequences drawn.”

—So you don't agree with the version that this was the meeting of two civilizations?

—No. What there was was the attempt for centuries to destroy the indigenous world: its language, its mode of production. They remain marginalized. What meeting? They are part of the nation, miscegenation exists, but that it was in the encounter between two cultures, no. There is an unresolved ethnic problem. The EZLN is right when it presents its proposals for autonomy and cultural regeneration. Not to fragment, but in order to unite the country. May the many nations that exist be unified. It is an example of the type of thesis that must be elaborated: old problems that require new solutions.

—What challenges does the communist movement face?

—The communist movement can be reborn. Not the same as before. Its ethical and political legacy, its work models, the traits of many of its militants, their experiences, must be put into play today to unify political life.

It is necessary to integrate ethics and politics. Without this, there will be no reconstruction of parties or a new evaluation of politics. The old approaches have to be modified according to the current moment. The proposals cannot lose the rhythm of the new times. Now the changes are faster. From this you can learn from the Chinese. The Chinese leadership is a very qualified, rigorous group, it has advanced from the recognition of mistakes. They seek a certain international harmony. A community of destinations. They don't just follow Marxism, but old schools of Humanism and Confucianism; that is, the ancestral knowledge of the peoples. We must resolve the concrete and concrete contradictions.”

I don't think that as Mexican socialists we should consider annihilation, devastation. What capitalism has to contribute to the new and future Mexico must be collected. You have to build the world.

—And what do you think of Xi Jinping's indefinite re-election policy?

—It's one of the debatable things, but you have to look at it coldly. If you look at the size of China's problems, the dimension of the great historical leap that they are making is enormous. Political control, in many cases, is absolute. They do not allow other parties to dispute power. That they express positions, yes. This in view of the need for a united country. No cracks. They already had them in the past. They were very expensive. You have to prevent them from showing up again. And do not rule out or disqualify that this is achieved perhaps not with rotation, but with giving more control to the most capable political group, the most trusted man, to cover and give stability to one stage of the change process.

—What other issues are at the center of your concerns today?

—The problem that worries me the most is the meeting of the needs that we have as a country and as a working class with the existence, the way of life and the concerns of today's youth.

Today's youth are more informed, highly productive, and more troubled than ever before. The perspective of its existence is mortgaged. It is entertained in many things. Information instruments attract, abstract, disconnect and alienate. But the need for popular and democratic solutions is vital to them. Or they will be condemned to always be poor, miserable, marginalized. Or destined for impossible consumerism, drug trafficking, hit men.”

Living in today's world, participating in solving the gigantic problems of peoples and individuals; Taking advantage of the advances in knowledge, technology, and the best values of culture is the great challenge of youth.

—By information tools, do you mean new technologies?

—New technologies provide information and misinformation; they can be used and are used for new forms of domination of consciences. The ruling class exercises its dominance ideologically in an increasingly sophisticated way.

They are going to control new branches, such as robotics, artificial intelligence, quantum information, biotechnology, based on the interests of small elites who benefit from property and drive human civilization.”

Profile

Marcos Leonel Posadas Segura

Marcos Leonel Posadas Segura (Tampico, Tamaulipas, Mexico, 1938), electrical worker at Petróleos Mexicanos, editor, journalist, politician. He entered the ranks of the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) since 1956. In 1964 he was elected as General Secretary of the Communist Youth of Mexico (JCM). Director of Opposition, official publication of the PCM. Founder of the Unified Socialist Parties of Mexico (PSUM) —where he held the Secretary of Organization and International Affairs—, Mexican Socialist (PMS) and of the Democratic Revolution (PRD). He has participated in the political groups Corriente del Socialismo Revolucionario, Fundación Comunista, Corriente del Socialismo Democrático and Dignidad Ciudadana. He currently works for the Mexican Communist Movement (MCM) and directs the weekly electronic publication Tribuna Comunista.